In a year in which the Oakland Police Department grappled with one of the worst scandals in its history, it also quietly accomplished something not seen in the city in decades: For the first time in more than 20 years, no one in Oakland was shot by a law enforcement officer.

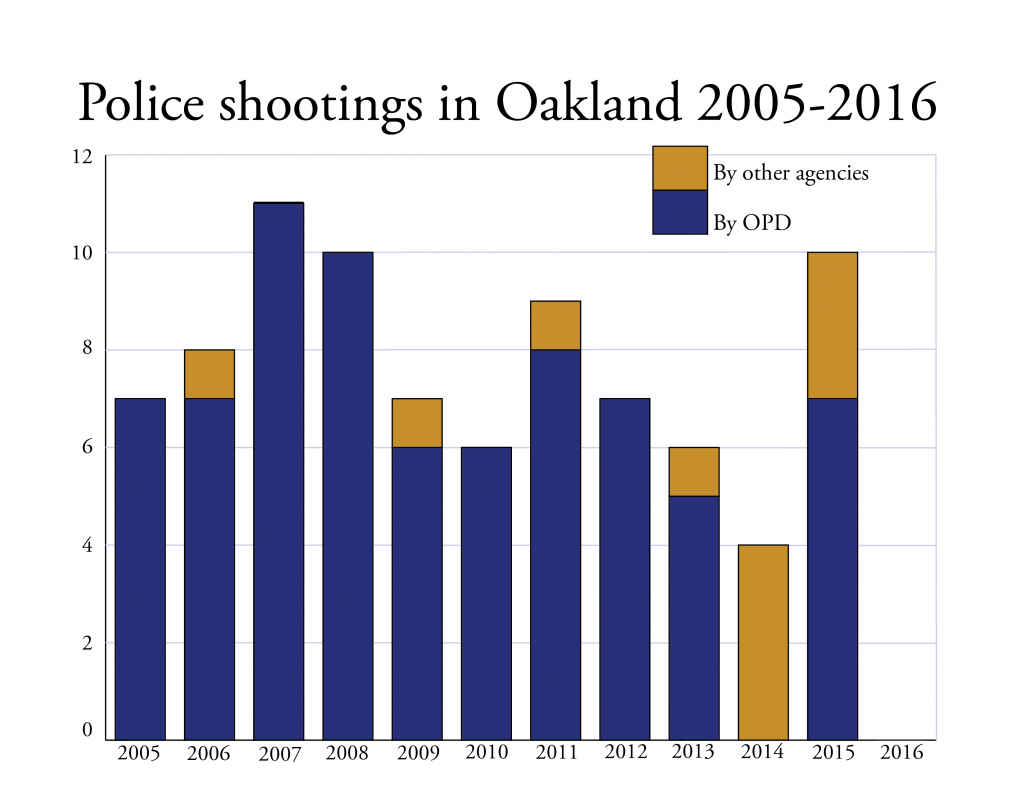

In fact, from Nov. 15, 2015, until Feb. 17, 2017, no law enforcement officer even fired a weapon within Oakland’s city limits. According to records collected by the independent reporting project Oakland Police Beat, Oakland has experienced multiple police shootings each year since 1993. Prior to 2014, the city averaged seven to eight shootings by police annually.

“As homicide commander, I truly appreciate the fewer number of officer-involved incidents,” said Oakland police Lt. Rob Rosin. “They can be high-profile. They demand a lot of resources. They are investigated extremely thoroughly by multiple parts of the department as well as the Alameda County District Attorney’s Office.”

The resources spent on investigating officer-involved shootings could be directed elsewhere, like investigating murders, Rosin added.

What exactly caused the decline in shootings is difficult to determine and could be attributable to changes in policy, training, and use of technology, and to fluctuations in the number of cops on the force. There’s also evidence that a surge in police shootings in 2015 may have been the result of attempts by OPD to rapidly increase staffing without thorough vetting and training—problems that seemed to have been addressed by 2016.

After making a number of court-ordered reforms stemming from a 2003 civil rights settlement, OPD began 2016 as a nationally recognized leader in modern policing practices. Use of force by Oakland cops had been declining steadily for some time, a trend the department has attributed to improved training and policy, such as phasing in the use of body-worn cameras starting in 2010. Oakland’s was one of the first departments in the country to start using body cameras, which record interactions with the public. In 2014, OPD became one of the first departments to deploy cameras to every officer.

Oakland cops also went a year without firing their weapons in 2014, but there were an unusual number of officers that year with other law enforcement agencies—some assisting Oakland—who fired on suspects in the city. That year, when Oakland’s police staffing dipped to precipitously low levels, plummeting to just 612 cops in April 2014, the department had to rely on extra crime suppression efforts from the California Highway Patrol and the Alameda County Sheriff’s Office. In January 2014, CHP officers shot and killed two suspects in Oakland on the same day while working as part of the Operation Impact task force to supplement the city’s depleted police department. Then in August, a county sheriff’s deputy fatally shot an unarmed robbery suspect during an Oakland police operation searching East Oakland backyards.

While the reduced Oakland police staffing wasn’t necessarily the cause of the shootings by outside agencies, it remains a historical anomaly. Since 2005, 11 suspects have been shot in the city by officers with outside agencies and seven of those shootings happened in 2014 and early 2015, according to data provided by Oakland police. Two others occurred after San Leandro police followed suspects onto dead-end streets in East Oakland; Yuvette Henderson was killed after running into Oakland while trying to evade Emeryville police; and Timothy Stout was wounded by a Contra Costa County District Attorney’s inspector serving a court order near Oakland airport.

In 2015, the number of shootings by Oakland police surged again. OPD’s ranks had swelled with rookies in 2014 and 2015, adding more than 200 new officers in about 20 months. And it was mostly rookies who fired on seven suspects, killing five, that year. According to Rosin, the majority of OPD officers now have fewer than four years experience due to an exodus of cops because of retirement, injuries, and transfers to other cities.

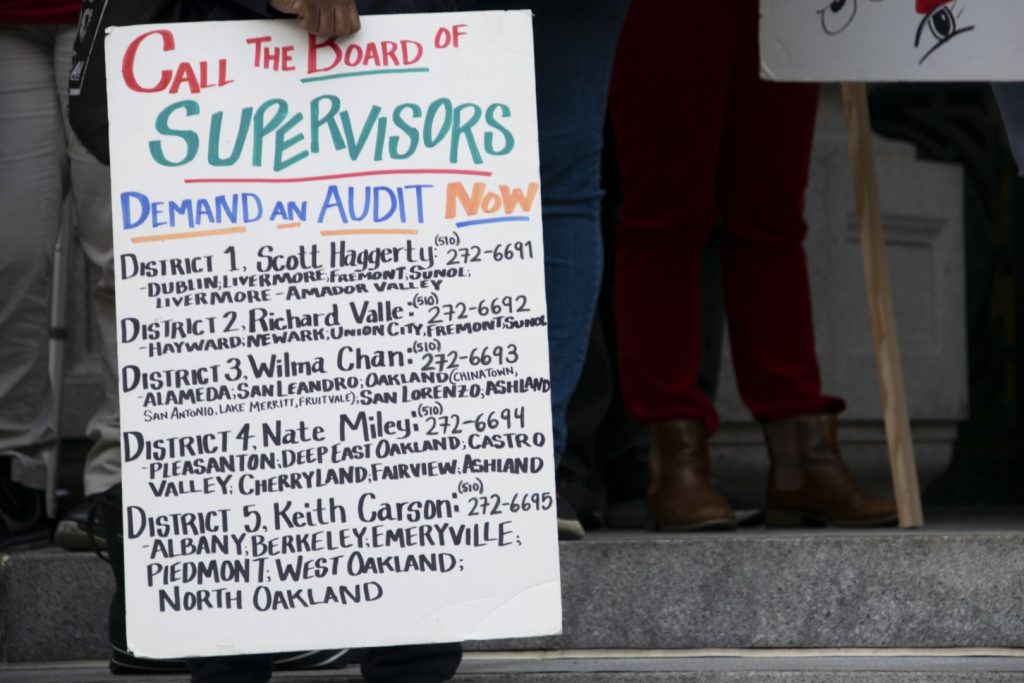

In 2016, a wide-reaching sexual exploitation scandal that also involved several rookies called into question the adequacy of the department’s training and recruitment practices, prompting an audit of the department and the city council to consider canceling police academies. Completed late in 2016, the audit examined “78 officers who had engaged in serious misconduct, received serious discipline or had otherwise engaged in unethical behavior since 2012,” and found that 17 percent of them had been fired from some previous employment, 45 percent had been turned down by some other agency before being hired by the Oakland Police Department, and two had previous criminal allegations for possession of a controlled substance other than marijuana.

The audit recommended several changes to the department’s recruitment and training processes, some of which had already been implemented by the time the report was made public—such as transferring the final hiring decision to the police chief, improved vetting, and expanding the background check team from four to eight officers.

Police spokesperson Officer Johnna Watson said that late in 2014 and early in 2015, the department started implementing better tools for recruitment, training, and monitoring performance. Part of that includes a computer matrix, installed in late 2014, that allows the department to track performance of new officers and how much training they might need.

“Are we doing things the best that we can do them?” Watson said. “It’s very difficult to take an internal look at yourself critically, and we asked ourselves, ‘Is this the best that we can do?’ And we saw areas that we could change and improve on.”

The sex abuse scandal that rocked the department in 2016 actually dated back to early in 2015. One of the officers who allegedly had sex in July 2015 with the teenage girl who went by the name Celeste Guap was a rookie: Giovanni LoVerde. He had graduated from the academy in November 2014, in the same class as Officer Nicole Rhodes, who fatally shot Demouria Hogg after he was found sleeping in a car with a gun beside him in June 2015, as well as Officer Joshua Barnard, who was one of four officers who shot and killed Richard Perkins after he approached them with an Airsoft pistol in November 2015.

Another officer who fired his gun in the Perkins case was Jonathan Cairo, one of 47 officers who graduated from the academy in April 2014. Also in that class was Karolina Zachoszcz, who broke the 2014 streak by Oakland officers when she shot at a man wielding golf clubs on Feb. 7, 2015, as well as James Ta’ai and Terryl Smith, who were both placed on leave in connection with the sex abuse scandal. Smith was later charged with five counts of improperly accessing a criminal database.

Only one of the four cops who shot Perkins was a veteran—Sgt. Joe Turner, who had been with the department for seven years at the time. Perkins was shot 11 times by four cops moments after approaching a group of police doing paperwork. There were at least 10 officers who drew their guns in the encounter and none turned on body-worn cameras before the shooting. It was the last police shooting in Oakland until this year.

Lt. Rosin said the department implemented several changes with an eye to preventing violent encounters between suspects and police officers, including adjusting the way officers handle foot pursuits and creating time and distance with suspects to avoid escalating encounters. Violent encounters often come when confrontations happen suddenly, potentially endangering the lives of suspects, officers, and bystanders.

“Those kinds of forced encounters are extremely volatile, and they can be violent, so we want to avoid that,” Rosin said. Oakland police officers’ training includes simulations of use-of-force scenarios that are used to critique performance.

On Feb. 17, 2017, the shooting drought was finally broken when an Oakland police officer shot and killed 32-year-old Jesse Enjaian. Enjaian had been walking around his East Oakland neighborhood with a rifle, firing on his neighbors, their cars, and at arriving officers. He continued walking around the neighborhood with the rifle for about 30 minutes while being filmed by news helicopters before an officer killed him.