Thomas Michael Henderson promised Oakland everything: He would bring thousands of new jobs to the city to fill its historic buildings, open a grocery store in West Oakland, and start hip new restaurants all over the Town. He garnered glowing profiles in local newspapers and The Wall Street Journal, set himself up with a brilliant view of the city from its most iconic building, and even threw out the first pitch at an Oakland A’s game.

The tall, lanky businessman came across as a bonafide Oakland booster, sincerely interested in helping the city thrive. He became politically active, too, hobnobbing with local politicians, cutting fat campaign donation checks, and dining on luxurious meals as he devised plans to create numerous business ventures with some of Oakland’s most prominent entrepreneurs and most dogged community activists.

According to many of Henderson’s former business partners and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, it was all a fraud.

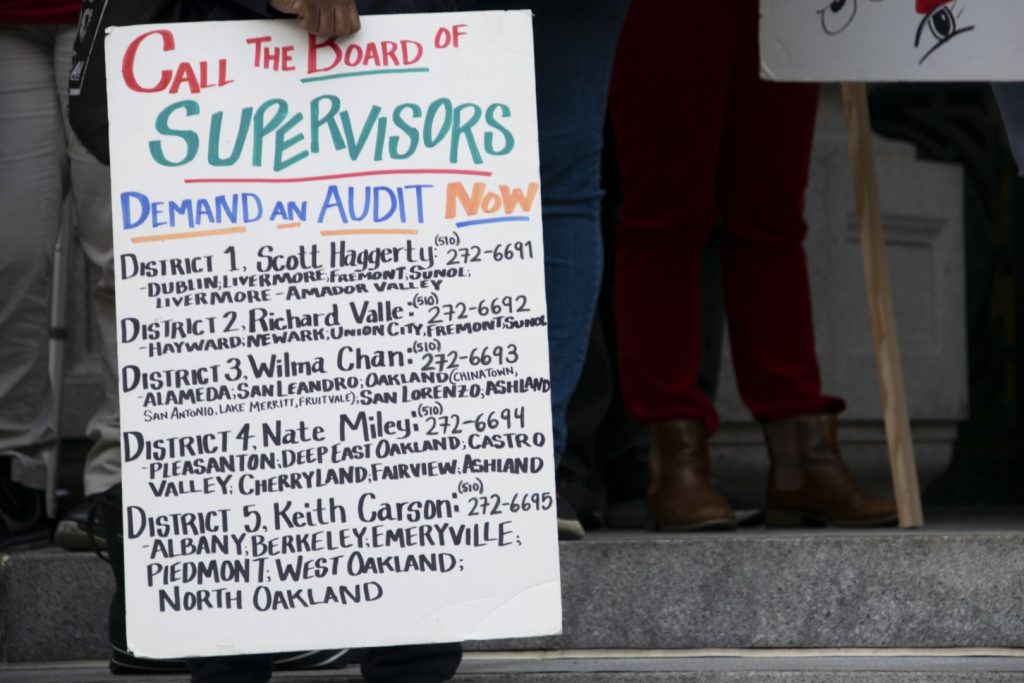

His former business partners and the SEC paint a picture of Henderson as a man out to enrich himself by taking millions of dollars from foreign investors seeking visas to the United States. The SEC sued Henderson for fraud on Jan. 17 after a series of business partners filed lawsuits accusing him of reneging on his agreements, hiding key financial information, and failing to pay back a $3.7 million loan from a West Oakland nonprofit.

Henderson was funding his businesses and his lavish lifestyle through a federal program that grants permanent residency in the United States to wealthy immigrants if they make an investment of $1 million or more — $500,000 for areas with high unemployment — and the investment creates at least 10 full-time jobs for American workers. The 27-year-old visa program, known as the EB-5, is designed to spur the domestic economy through foreign investment.

In recent years, the program’s popularity has soared, jumping from $240 million in investments in 2007 to $4.4 billion in 2015, according to a report by financial adviser Brandlin & Associates. And as the visa program has grown, the SEC has warned of scams in which unscrupulous investors make false promises to immigrants who are eager for green cards.

To attract foreign investors, Henderson used slick marketing materials detailing his many East Bay business proposals. From 2010 through 2016, he raised a total of $115 million in capital contributions from 215 investors, primarily from China.

According to interviews with his former business partners, allegations they and the SEC have made against him in court, and interviews with former business associates and others who interacted with him during his extensive affairs in Oakland, Henderson moved the EB-5 money from company to company in an elaborate shell game: first setting up a nursing facility, then a series of CallSocket call centers, and then proposing to develop a grocery store, among several other ventures. At first, he would do what he promised but then would misappropriate some of the funds he collected for expensive purchases, according to the SEC and his former business partners.

Records show that Henderson spent $42 million on real estate in Oakland from 2012 to 2014, gobbling up historic downtown landmarks like the Tribune Tower, the former I. Magnin building, and the Dufwin Theatre. He also bought a $1.4 million home in Oakland’s Upper Lakeshore area. But he created few jobs; the Tribune building still needs repairs; most of his planned restaurants never opened; and West Oakland still needs a grocery store.

Henderson declined to be interviewed for this report through his attorney, Gilbert Serota. In an email, Serota wrote, “Mr. Henderson is currently engaged in defending himself against allegations by the SEC and others that he views as based on inaccurate facts and mischaracterizations of his conduct. Because of the ongoing litigation, we have advised him not to be interviewed by any press or media.”

The ongoing litigation against Henderson is extensive and has left a tangled web of competing interests, all trying to recover what they can from his tattered empire. Assets from his many companies have been placed under court control, throwing the future of his businesses in doubt, delaying development of his properties, and angering investors. Many investors are also worried about potentially facing deportation.

In May 2016, as Alameda County Superior Court Judge Julia Spain worked to unravel Henderson’s complex network of business dealings, she noted during a hearing how easy it is for unscrupulous business people to game the EB-5 program. She pointed out that the law only requires that a business be temporarily viable for the foreign investors to get their green cards. “If you can keep a sham up for five years,” she said, “and all your investors get their green cards, mission accomplished.”

Tom Henderson frequently pointed to his background as an East Bay native and successful businessman in order to sell his ambitious proposals, but large chunks of his biography are mysterious. He told the San Francisco Business Times that he grew up in Piedmont. According to his former LinkedIn profile, which was deleted earlier this year, he had a basketball scholarship to attend UC Berkeley from 1966 to 1970 and earned a degree in business administration.

He started a seafood importing business, Avalon Bay Foods Inc., in the 1970s that he ran until the 1990s, according to a short biography on the website of his current company, San Francisco Regional Center. The bio claims that he grew Avalon to thousands of employees through joint ventures in Asian countries and with British Petroleum before selling it to a “multi-national strategic buyer.” Avalon Bay Foods appears to no longer exist; no businesses are registered with that name either with the SEC or with the state of California.click to enlarge

To former East Bay business associates and acquaintances, Henderson came across as earnestly interested in growing the local economy and talked about how he wanted to bring jobs to Oakland and help revitalize the city. He also spoke warmly of the EB-5 investors, referring to them as “family” whom he wanted to help move to the United States and provide better education and opportunity for their children.

Despite Henderson’s 6-foot-5 frame, he isn’t a commanding or intimidating presence; rather, he is generally quiet and a good listener, former associates and acquaintances said. But he could be aggressive when challenged and at times was prone to shouting obscenities.

Henderson appears to have made his first foray with the EB-5 visa program in the East Bay in 2009 when he approached Alameda nursing facility administrator Shirley Ma with the idea of starting a skilled nursing facility with foreign investor funds. Ma had operated a nursing facility on the Island for 21 years and agreed to partner with Henderson, with her running the nursing facility and him recruiting the investors.

In early 2010, Ma found a nursing home east of Lake Merritt called the Oakland Springs Care Center that was at risk of losing its license. She described it in court filings as a “failing nursing home in a dilapidated facility.” She started the rigorous application process to purchase the nursing home and prove she was qualified to run it.

Later that year, Henderson formed San Francisco Regional Center LLC with his two sons, Matthew and Michael, to begin soliciting EB-5 investors.

The EB-5 program, or the employment-based visa program, was signed into law by President George H.W. Bush as part of the federal Immigration Act of 1990 in an effort to spur U.S. job growth.

In 2011, Allan Young, a venture capitalist interested in technology, was introduced to Henderson through Max Shapiro, a San Francisco-based recruiter who was once a talent scout for the Phoenix Suns basketball team. At the time, Henderson was looking for ideas of what kind of businesses to start with EB-5 money, according to a lawsuit Young filed against Henderson five years later. Young came up with the idea of starting a call center, and they became partners in the new business, called CallSocket. Shapiro took a 5-percent stake.

After purchasing the nursing home, Ma began making extensive renovations to its interior, buying new beds and central heating and cooling systems, replacing the electrical system, and bringing the facility into compliance with building codes. It took nearly two years and $1.7 million to complete the overhaul. During that time, Henderson raised $12.5 million from 25 EB-5 investors for the project.

But Ma never saw all the money. In December 2011, Henderson bought the Tribune Tower for $8 million, a move that drew him considerable attention both for the low price and for his ambitious plans.

In SEC filings, Henderson admitted that he used $1.3 million in funds he raised for the nursing home to purchase the tower, but Ma said he told her something different at the time. “When I asked if the purchase of the Tribune Building was an EB-5 project,” she stated in court filings, “Henderson claimed it was a personal investment which he was purchasing through a private lender.”

It would not be the only allegation of a scam involving the historic tower.

The six-story base of what would become the Tribune Tower was built in 1906 as a Breuners furniture store. In 1908, the Oakland Tribune newspaper moved in. The 22-story tower — with its tapered copper green roof, clock, and TRIBUNE letters — was designed by Stanford alum Edward T. Foulkes and constructed in 1922. The newspaper operated there for more than 80 years until the building was damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. The paper moved to Jack London Square, and the tower was left vacant for much of the 1990s.

John Protopappas of Madison Park Financial Corp. bought the tower in 1995 and started four years of renovations. The Tribune moved back in when the tower reopened in 1999, but departed again for a building near the Oakland Coliseum in 2007, shortly after Madison Park sold the tower to two business partners based in Southern California, Edward Kislinger and Eric Waterman. Kislinger and Waterman had paid $15.3 million, but when the Tribune moved, they were left with a building that was 86 percent vacant. They defaulted on the mortgage, and the building was placed in receivership. That allowed Henderson to scoop it up for only $8 million.

The splashy purchase brought him lots of attention. In February 2012, The Wall Street Journal published an enthusiastic profile of Henderson that highlighted his purchase of the tower and his mission to create 2,000 jobs in two years but warned of a lack of regulation and exaggerated promises in the EB-5 visa program. The reporter, Bobby White, later went on to work for Henderson on his grocery store project.

In March 2012, Henderson joined forces with respected Oakland restaurateur Chris Pastena. They had met through a mutual friend late in 2010, after Pastena had recently made a name for himself by opening the popular Chop Bar in the Jack London district. Pastena signed on to work with Henderson to develop a restaurant with EB-5 funds.

In a recent interview, Pastena said he was originally persuaded by Henderson’s emphasis on jobs and creating a plan to grow the community. “I’m invested in Oakland and its future and hopefully a positive contributor to it, and it seemed like he was on that same path,” Pastena said.

When Pastena was offered an opportunity in 2012 to open a restaurant in the Waterfront Hotel at Jack London Square, he brought the idea to Henderson and they opened Lungomare, a high-end Cal-Italian eatery, in February 2013. They also came up with a plan to open a restaurant in the base of the Tribune Tower and opened the Tribune Tavern in April of that year. Pastena said he was working 80 hours or more a week at the time, setting up the new restaurants. Henderson sank $3.8 million in capital from EB-5 investors into the two eateries, according to the SEC.

Local politicians like then-Mayor Jean Quan also attended social events to tour the historic tower. Quan, the first Chinese-American woman to be mayor of a major U.S. city, made a point of bringing in Chinese investors to Oakland and said in an interview that she is very familiar with the EB-5 program. She said she would see Henderson around at other business events, such as those hosted by the Oakland Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce.

Although Quan stressed that many EB-5 ventures have had a positive impact on the local economy, she said she had concerns at the time about the breadth of Henderson’s portfolio. “It sounded to me that he took up so much property, that he was overextended, and I always wondered about that,” she said. “The fact that he owned a lot of downtown property was something we had to deal with.”

Henderson donated $700 to Quan’s reelection campaign in December 2013, but two weeks later, he donated $1,400 to Quan’s rival, then-city Councilmember Libby Schaaf. In June, he donated $1,400 to then-City Auditor Courtney Ruby’s campaign for mayor. Schaaf ultimately prevailed that November and at the time had positive things to say about Henderson’s business activities.

But few people knew then that Pastena had recently become the first of Henderson’s Oakland business partners to sue him. In his lawsuit, Pastena said Henderson would bring potential EB-5 investors to Chop Bar to impress them and use Pastena’s name and involvement as an assurance of Henderson’s own business potential.

Henderson also had set himself up rent-free at the top of the Tribune Tower and built a lounge to entertain investors. Tenants with ties to Henderson operated out of the tower rent-free as well. During a hearing last year, Susan Uecker, who was appointed by Judge Spain as the receiver overseeing Henderson’s businesses as a result of the Young lawsuit, said the majority of the tenants in the tower were operating rent-free, while others were given “sweetheart” deals, like Henderson’s own lawyer, Leeds Diston, whose firm had an office on the ninth floor for only $1 a year. Among the businesses operating rent-free was the Tribune Tavern, where Henderson entertained investors.

But parts of the building were in disrepair. One tenant, Dan Cohen of Full Court Press Communications, said there were multiple elevator failures during Henderson’s ownership of the building, and a colleague once got stuck between floors. “She was terrified, and none of us really ever trusted that one again. I know he tried and was as frustrated as the rest of us, but it took a long while to get it right,” Cohen said of Henderson.

Henderson also kept buying Oakland real estate. In October 2013, he purchased the Community Bank Building at 1750 Broadway for $797,000. A month later, he bought a warehouse at 1700 20th Street for $8.25 million. In December of that year, he purchased the Dufwin Theatre at 519 17th Street for $4.3 million. And the following June, he bought the I. Magnin Building at 2001 Broadway for $9.8 million. For each of the purchases, Henderson later admitted he used funds raised for his EB-5 ventures.

His talk of creating jobs and opportunity came across to many as genuine. In meetings, he would listen carefully, ask questions, and solicit opinions. His apparently selfless motives brought him accolades from politicians and reporters and he was treated as a hero in Oakland.

In July 2013, the San Francisco Business Times published a profile, stating that Henderson’s first wave of 200 investors — contributing $500,000 each — was just the beginning, and he’d soon be raking in $100 million in EB-5 money and creating 2,000 jobs each year. “The first question I ask is, ‘How many jobs does it create?'” Henderson told the paper. “I’m focused on the whole community. I’m not just a white guy who grew up in Piedmont who wants to make a quick buck. I’m not focused on making money.”

He threw the first pitch at an Oakland A’s game later that month, teaming with Oaklandish to sponsor a T-shirt giveaway: a throwback shirt featuring star players from the late 1960s and early ’70s, like Rollie Fingers, Catfish Hunter, and Vida Blue.

The Oakland Tribune published another profile in October 2013 reporting on Henderson’s ambitious plans, like opening three grocery stores in West Oakland and a food factory in East Oakland. It quoted Young calling him a “savvy businessman.”

Young didn’t know at the time that Henderson’s house of cards would soon collapse.

In January 2014, Shirley Ma took out a $2 million loan to continue maintaining her nursing home, because Henderson had stopped paying her EB-5 funds at the end of 2013, according to court filings. She signed the loan herself and continued growing her business.

Pastena sued Henderson in August 2014, alleging that Henderson had intended to force him out of the Tribune Tavern and the venture had been a ploy to increase the value of the building after Pastena, the only partner with restaurant experience, designed and built a successful ground-floor restaurant.

According to court documents, the Henderson-Pastena partnership had badly deteriorated: They got into disagreements, including about the expensive complimentary meals and drinks Henderson took for himself, his friends, and other business partners, which Pastena said caused the restaurants to operate at a loss. Pastena found Henderson increasingly confrontational and secretive. And Henderson started accusing Pastena of improper conduct, like co-mingling funds from Lungomare and Tribune Tavern with Chop Bar. Eventually, Henderson said he wanted to end their partnership and threatened to sue Pastena, while working to conceal financial information about the businesses.

They reached a settlement by the end of 2014 that called for Pastena to retain control of Lungomare and Henderson taking the Tribune Tavern. Pastena declined to discuss the specifics of the settlement but said, “He owned the Tribune building, so the last thing I wanted to be is his tenant.”

But even as he dealt with that legal fight, Henderson was still hatching other EB-5-funded plans. In June 2014, he started working with a West Oakland nonprofit, the West Oakland Marketplace Advancement Company, or WOMAC. It had been trying to open a grocery store in the neighborhood for years. West Oakland is classified as a food desert by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and most of its residents travel elsewhere to buy groceries.

City Councilmember Lynette Gibson McElhaney, West Oakland-Downtown, recommended Henderson as a potential partner in the grocery store project with WOMAC at the Jack London Gateway Shopping Center at 7th and Market streets. In an email to the Express, Gibson McElhaney said she didn’t know Henderson well. “I actually cautioned the non-profit leaders to do their own due diligence and encouraged them to seek out other EB-5 investors,” she wrote. “They made a decision to move forward with Tom but did so without further input from me.”

Ron Muhammad of WOMAC, which is affiliated with the community at the Acorn housing projects, said in an interview that he was intrigued by Henderson’s promise of jobs and community development. With all the businesses Henderson was already involved in, it appeared that opening a grocery store would be a slam dunk. It also gave WOMAC the opportunity to buy out their partners at the center. “Our other two partners at the time never thought that we would have the opportunity to buy them out and have the opportunity to develop that site,” Muhammad said. “He sold the idea that he could help us make it a reality and bring forth a grocery store.”

That December, Henderson engineered a sequence of deals to form a new company that owned the shopping center, with his company, San Francisco Regional Center, owning 75 percent and WOMAC owning the remaining 25 percent. Henderson obtained a $6.9 million loan for the purchase and borrowed $3.7 million from WOMAC, which he promised he would begin paying back in February 2015, according to court filings.

His purchase of the property earned him another flurry of positive coverage. In a January 2015 report in the Tribune, Henderson said the market would have wooden floors, French doors, and an in-house nutritionist but would remain affordable. He talked about opening another restaurant in the plaza as well. But the newspaper report also pointed out that he was way behind on his job creation obligations under the EB-5 program and that some of his projects had not worked out as planned.

That July, Young — Henderson’s partner in CallSocket — filed a lawsuit alleging that Henderson had prevented him from accessing financial information about their call center companies and had been diverting funds for personal use. Young and Henderson had formed six CallSocket companies to raise EB-5 investments and manage the call centers, but for two years Young had found himself frozen out of his businesses finances. The lawsuit accused Henderson and his sons of misappropriating $53.5 million raised for running the CallSocket call centers, diverting it either to themselves, into real estate investments, or to 16 other companies they controlled.

By early 2016, Henderson’s CallSocket call centers were bleeding money. Two were operating out of the fourth and sixth floors of the Tribune Tower, and the partners had intended to establish a third. The first call center eventually grew to 105 employees while the second had 65, but many of the employees in the second company were only hired after Young sued Henderson. Henderson had been soliciting investors for the second call center with a brochure that promised profitability within two years.

WOMAC, meanwhile, sued Henderson in September 2015, saying he had not made any payments toward the $3.7 million loan and had taken no action to rehabilitate the shopping center. In the Tribune, Henderson blamed WOMAC for the delays, accusing the nonprofit of stopping the project for its own gain “at the demise of the community.”

Yet Henderson continued recruiting investors for the stalled project. According to the SEC, from November 2015 to September 2016, Henderson raised $2 million in capital investments for the planned grocery store but made no progress on it. Instead, he had been diverting the funds to other ventures.

In March 2016, Henderson sold the I. Magnin building for $19.5 million — double the $9.8 million that he paid in 2013. Then just after the sale, Judge Spain ordered all of the call center businesses’ assets to be placed under court control as part of Young’s legal action, finding the property and funds to be “in danger of being lost, removed, or materially injured.”

The property seized included the proceeds from the I. Magnin building’s sale as well as most of Henderson’s business real estate, including the Dufwin Theatre and the Tribune Tower.

The court-appointed receiver, Susan Uecker, sold the Tribune Tower to Harvest Properties for $20.4 million in December 2016 in an effort to pay back investors. Harvest has been working on renovations and recently completed a lobby upgrade and is about to begin work on seismic improvements, according to senior property manager Kristy Michelmore.

“In the coming months,” Michelmore wrote in an email, “we will also be completing an elevator modernization, waterproofing repairs, and some market ready work on a few of the lower floors.”

But Henderson’s numerous other Oakland businesses would not be so easy to fix.

Two months after the SEC sued Henderson for fraud in January 2017 in federal court, U.S. District Judge Richard Seeborg appointed Uecker, who had been serving as the receiver in state court, to be the federal receiver. Seeborg placed Henderson’s remaining companies under Uecker’s control, including the West Oakland grocery store property and the nursing facility. Most of the stakeholders argued in filings against the appointment of a federal receiver, with Young seeking to pursue his own litigation, EB-5 investors concerned that their green cards could be in jeopardy, and others worried about the continued operation of their businesses.

Ma, still operating her nursing facility in Oakland, said in court filings that she expects to employ 185 people by June 2018 and that her business continues to grow. She said she is in the process of implementing a new service to provide dialysis treatment for subacute patients, which would be the first facility of its kind in Northern California. Ma said in court filings that she bought Henderson’s share of the nursing care company and is now the sole owner. She concluded that Henderson had misappropriated $4.7 million of the EB-5 funds intended for the nursing home.

Judge Spain ordered the closure of Henderson’s first call center business last year. And though Henderson projected the second call center to have hundreds of employees within a few years, after court-ordered downsizing, only about a dozen employees were left as of June, and it was still operating out of the fourth floor of the Tribune Tower. A third call center never materialized, despite Henderson raising up to $21 million for it.

A logistics business is still operating out of a West Oakland warehouse on 20th Street that Henderson purchased using funds raised for the call center. Henderson had projected it would create nearly 600 jobs either directly or indirectly by this year, according to federal court records. But by March, it had only 29 employees with little hope of meeting the requirements for all 40 of its investors to immigrate.

In addition to selling the Tribune Tower, Uecker facilitated the sale of Henderson’s other downtown buildings, generating a total of $38 million. The shopping plaza in West Oakland remains under court control, but on Oct. 5, Judge Seeborg approved Uecker’s request to list the building for sale over WOMAC’s objections.

Uecker obtained an evaluation by Colliers International valuing the property at $10.4 million. It includes a McDonald’s restaurant with a fixed-rate lease through 2030, which Colliers argued would be an important source of revenue for any buyer seeking to develop the run-down shopping center and attract new tenants. The analysis also found that a deed restriction established by the city of Oakland requiring a grocery store there would be a liability for the property, suggesting a new mixed-use development would be best for the site. According to Colliers, the city has shown no flexibility in waiving the grocery store requirement and in fact is seeking $500,000 in damages because the project remains stalled.

In court filings, attorneys for WOMAC bristled at the suggestion that the grocery store requirement was a liability, saying it would be an important anchor tenant in revitalizing the plaza. But at this point, it seems likely that the effort to pay back Henderson’s investors has effectively wrested the plaza from community control.

WOMAC’s manager, Janet Patterson, stressed in an interview that the nonprofit took no money from Henderson and said she was frustrated that they were now caught in the middle of the legal fight between Henderson and the federal government. “We don’t think it’s fair,” she said. “But such is life, and we are here wondering just like anyone else.”

Perhaps no one is wondering more than the foreign investors who gave millions to Henderson thinking they would become permanent U.S. residents.

Henderson’s 215 EB-5 investors are now in various stages of immigration, a process that can take eight years or more. Some early investors have become lawful permanent residents, others are only in the beginning stages, and many are stuck in limbo, having moved to the United States only to apparently watch their prospects for finishing the process wane because of Henderson’s troubles.

Many of the foreign investors wrote letters to the court asking it to maintain or even grow the businesses and keep them out of receivership. One investor in the nursing home wrote that he had moved to Livermore and his daughter had recently graduated from the University of Virginia and had accepted a job in Manhattan. He worried that the receivership would place his hopes for a green card in jeopardy. An investor in the warehouse business wrote that in March, his family had been granted conditional green cards and he planned to resettle in Davis, enrolling his daughter in middle school there.

Whether Henderson will face further accountability remains unclear. He hasn’t personally had to declare bankruptcy, and he hasn’t been charged with a crime. However, similar cases have led to criminal charges, such as for Anshoo Sethi of Chicago, who was sentenced to three years in prison in February for misrepresentations when he solicited EB-5 investors for a hotel project that never materialized.

Henderson still has his four-bedroom, 2,766-square-foot home near Oak Grove Park in Oakland. It hasn’t been placed in receivership, despite the SEC alleging that he used about $346,000 in CallSocket funds toward the $1.4 million purchase price. (Henderson has denied this in court documents.) The house sits on a 4,791-square-foot lot, with three full bathrooms and Caeserstone quartz counters. The listing notice from when Henderson bought the home in 2014 reported that the house, built in 1918, had been recently renovated to “preserve its original feel.”

It’s one of the last assets that Tom Henderson still owns in Oakland.

![[Tribune Tower building]](https://www.oaklandreporter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/tribune-tower-13th-street.jpg)