In early October, the city of Oakland put the finishing touches on its third Tuff Shed camp. The small yard of 20 plastic sheds, each about 136 square feet, was built as temporary housing for 40 homeless people who had been camping around Lake Merritt. Two people share each shed, sleeping on a narrow cot and separated by a curtain.

The city started its Tuff Shed shelter experiment with its first camp downtown at Sixth and Brush streets last year, followed by a second camp at 27th Street and Northgate Avenue, near the Interstate 980 freeway. But its third camp’s location raised questions with some observers and city officials: in the shadow of the old Henry J. Kaiser Convention Center, a massive 215,000-square-foot building owned by the city that has been vacant since 2005.

“We specifically had a question about the Kaiser Convention Center,” Councilmember Rebecca Kaplan said at a council Life Enrichment Committee hearing on homelessness on Sept. 11, after several speakers questioned the city’s commitment to finding housing for homeless people. “The auditorium side, which currently has no plan for any use that is underway, has been used for emergency housing after fires and earthquakes.”

Kaplan asked for an update to the status of development plans for the building. The city entered an exclusive negotiating agreement with Orton Development in 2015 to lease the space from the city and make extensive improvements. Orton plans to turn it into office space with a cafe or restaurant and to restore the 1,900-seat Calvin Simmons Theater as a performing arts space. The larger 6,000-seat auditorium, once a premier venue for music and sports, would be renovated as an open mezzanine.

But the exclusive negotiating agreement expired early last year and was not extended. Orton’s website indicates the building would open early in 2019, but so far, no work has begun. Assistant City Administrator Joe DeVries indicated that the Tuff Shed camp’s location, just steps away from the entrance to the Calvin Simmons Theater, would not interfere with construction on the building whenever it begins.

For now, city officials say the condition of the building is too poor to be used for anything.

“The building is in disrepair,” said Kelley Kahn, a policy director in Mayor Libby Schaaf’s office who has been working on the restoration project for years. “It is considered by the fire marshal to be red-tagged. The building’s systems are inoperable or in disrepair, so there’s no plumbing, water, electrical, or HVAC.”

Since the city stopped using the building in 2005, it’s been broken into multiple times, including by thieves who have stripped out copper wire to sell. That has left parts of the building with exposed wires. Even when it was operational, it wasn’t fully up to code and required structural and seismic work. The city has estimated that just getting the basic systems operational for the arena would cost $10 million. Orton’s proposed rehabilitation is expected to cost about $50 million.

“It’s a long, complicated, expensive project with local, state and federal review processes at play,” Kahn said.

Kahn pointed out that the expired exclusive negotiating agreement is mainly to protect Orton and prevent the city from finding a different partner for the project. “Orton has been making good progress and is getting close to the project approvals they’re going to need to start construction, so the city has no plans to start over or rebid the work,” she said.

While the project is behind schedule, city officials are still hopeful that construction can start next year. Orton representatives gave a presentation to the Landmarks Preservation Advisory Board in February, saying that they are seeking to have the building placed on the National Register of Historic Places to take advantage of the tax benefits. The project could appear before the city council in February or March next year, construction could begin in late summer or fall 2019, and the building would open in spring or summer of 2021.

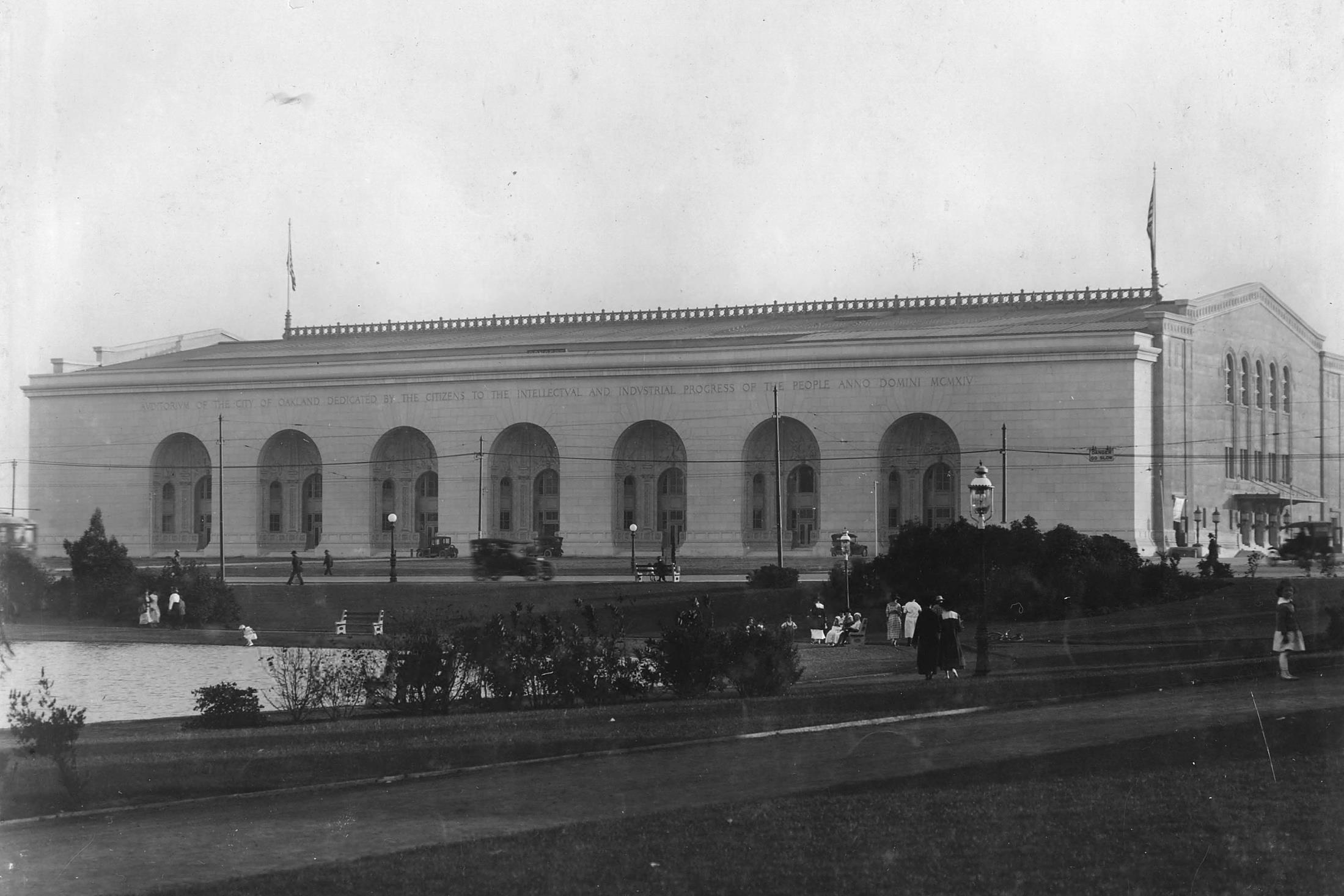

Although the huge, distinctive building, which, most recently has served as a backdrop for Golden State Warriors’ championship parade celebrations, is not on the national register, it has a rich history. The Oakland Municipal Auditorium opened in 1915 after Oakland voters approved two rounds of bond measures, passing the second by a razor-thin margin of only 139 votes over the necessary two-thirds majority. The building was designed by a team that included John J. Donovan, who also supervised the construction of Oakland City Hall and helped design three branch libraries constructed through grants from industrialist Andrew Carnegie.

The building was praised after it opened and even hosted President Woodrow Wilson in 1919. It proved valuable in 1918, when it served as a makeshift hospital during the flu pandemic. But even in its early days, operating the venue was expensive for the city. In 1920, news reports indicated that the city had been losing thousands of dollars on the auditorium. By 1922, a report by the East Bay Water Co. indicated that revenue had finally exceeded expenses.

In 1959, the voters were again asked to approve $925,000 in bonds to modernize the auditorium, the first bonds issued since its initial construction. It hosted a wildly diverse range of activities, from boxing and wrestling matches to the Harlem Globetrotters to midget auto racing to the Grateful Dead to opera and ballet. In 1924, it was the site of a large Ku Klux Klan rally; in 1962, Martin Luther King Jr. spoke there to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation.

But it remained expensive to operate. In 1974, the city considered tearing it down to build student housing for Laney College. In 1981, Oakland sold the neighboring museum building and leased it back to raise funds to rehabilitate the auditorium. Around that time it was renamed the Henry J. Kaiser Convention Center, after the industrialist who eventually founded Kaiser Permanente to provide health care for his workers.

By the late 1990s, it was becoming more difficult to host concerts there. Promoters told the East Bay Express in 1998 that it was more expensive to hold events there than in comparable venues elsewhere in the Bay Area, and so they avoided it. In 2005, the city council voted to shutter it because operating it was too costly.

In 2006, voters were asked to approve $148 million in bonds to convert the building into the city’s main library. Oakland voters had voted overwhelmingly to approve nearly $200 million in improvements to the lake in 2002, but the measure to renovate the auditorium fell just short of the necessary two-thirds majority.

Since then, the building has fallen into disrepair. A group of activists with Occupy Oakland attempted to take over the building and turn it into a community center in 2012, declaring Jan. 28 as “Move-In Day,” an effort that led to street battles with police and more than 400 arrests.

Some activists would have preferred that Occupy Oakland target a different building: the Miller Avenue branch library, one of the historic Carnegie libraries that was closed and left vacant since the late 1980s. Months after Move-In Day, a group of activists attempted to reopen the library, but were forcibly evicted by police. However, squatters continued to enter and use the library over the years; it burned last year and again this year and, just after turning 100 years old, it was finally demolished.

The Henry J. Kaiser Convention Center sits on the shore of the rejuvenated Lake Merritt, where the south end is bustling with activity after Measure DD enabled the city to build new parks and pedestrian walkways there. But despite its iconic and intrinsic place in Oakland’s history, including for emergency services, it has no use now. Orton is its last hope.

![[Tribune Tower building]](https://www.oaklandreporter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/tribune-tower-13th-street-1024x685.jpg)