More than 20 housing justice activists, including six homeless Oakland residents, protested outside of Mayor Libby Schaaf’s home last Monday to demand shelter and improved sanitation services for the more than 100 residents living unsheltered on or near Wood Street in West Oakland in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The group also demanded a decrease in police presence, which residents say has increased sharply since Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered California residents to shelter in place last month.

“I voted for [Mayor Libby Schaaf] because I met her on Wood Street and she said that she was going to do what she could to get the city to employ a lot of homeless people and give us resources in order to keep clean so that if we got interviews for jobs, we could be presentable,” said Lamonte Ford, a homeless resident who currently lives on Wood Street. Ford was born in Oakland and has spent most of his life here.

“I think she’s dropped the ball a lot,” said Ford. “I haven’t seen her since today during the protest at her home. I think she doesn’t really care about us. She just wanted a vote.”

Ford said when he’s tried to live as a homeless person in other parts of Oakland, police have repeatedly directed him towards Wood Street. But he doesn’t have access to the services he needs to be clean enough there as the city doesn’t provide ways to wash his hands or drink water.

“The bathrooms that are provided are not kept or maintained at all. They’re filthy and I’m scared to use them,” said Ford.

The urgency of homeless people being able to have their own space and maintain sanitary conditions has heightened since the COVID-19 pandemic, especially since a homeless shelter in San Francisco recently had an outbreak where 92 residents tested positive for the virus.

Oakland Reporter emailed Oakland’s Policy Director, Peter Radu, and asked if the city planned to increase sanitation services to residents who live on Wood Street but did not receive a reply.

Dayton Andrews, a member of The United Front Against Displacement, which organized the protest, carried a sign that read, “It’s actually very simple. House people or kill people.”

Andrews and the other protestors arrived at Schaaf’s home around 5 p.m., right when she also arrived and stepped out of her car. Schaaf did not meet with the group but asked “are you alright with me going inside the house?” and went into her home.

Speaking outside of Schaaf’s home with a microphone attached to an amplifier, Andrews emphasized the importance of activists still coming together to demand that all people can be sheltered while the COVID-19 pandemic continues.

“We’re here today in defiance, not of public health and safety, but in defiance of the message from our government that tells us to stay out of these streets, to trust them that they’re going to handle this crisis,” said Andrews.

Activists took precautions to lessen the likelihood of spreading COVID-19 during the protest. All who participated wore masks. While some activists got out of cars to speak, show signs, or address Schaaf directly, the majority stayed in their cars.

Andrews and the UFAD have built three hand washing stations and three water storage tanks that can provide drinking water to residents at Wood Street. But the group is only able so far to provide these services to a small portion of the residents as the total number of people who need them is too great.

Kellie Castillo-Stockley, a woman who now lives on Wood Street as she’s recently become homeless, has lived in the Bay Area for 25 years. She said if it weren’t for volunteers, “there would be no water where I’m at.”

Castillo-Stockley also said she’s driven around Oakland and seen much smaller communities of homeless people have wash stations and bathrooms while Wood Street’s residents don’t. One community of less than five tents which sits outside of Oakland’s Veterans memorial building and close to Whole Foods and Lake Merritt has a hand washing station and two toilets.

“We just want to make our voices heard,” said Jessica Bailey when Oakland Reporter asked her why she joined the protest.

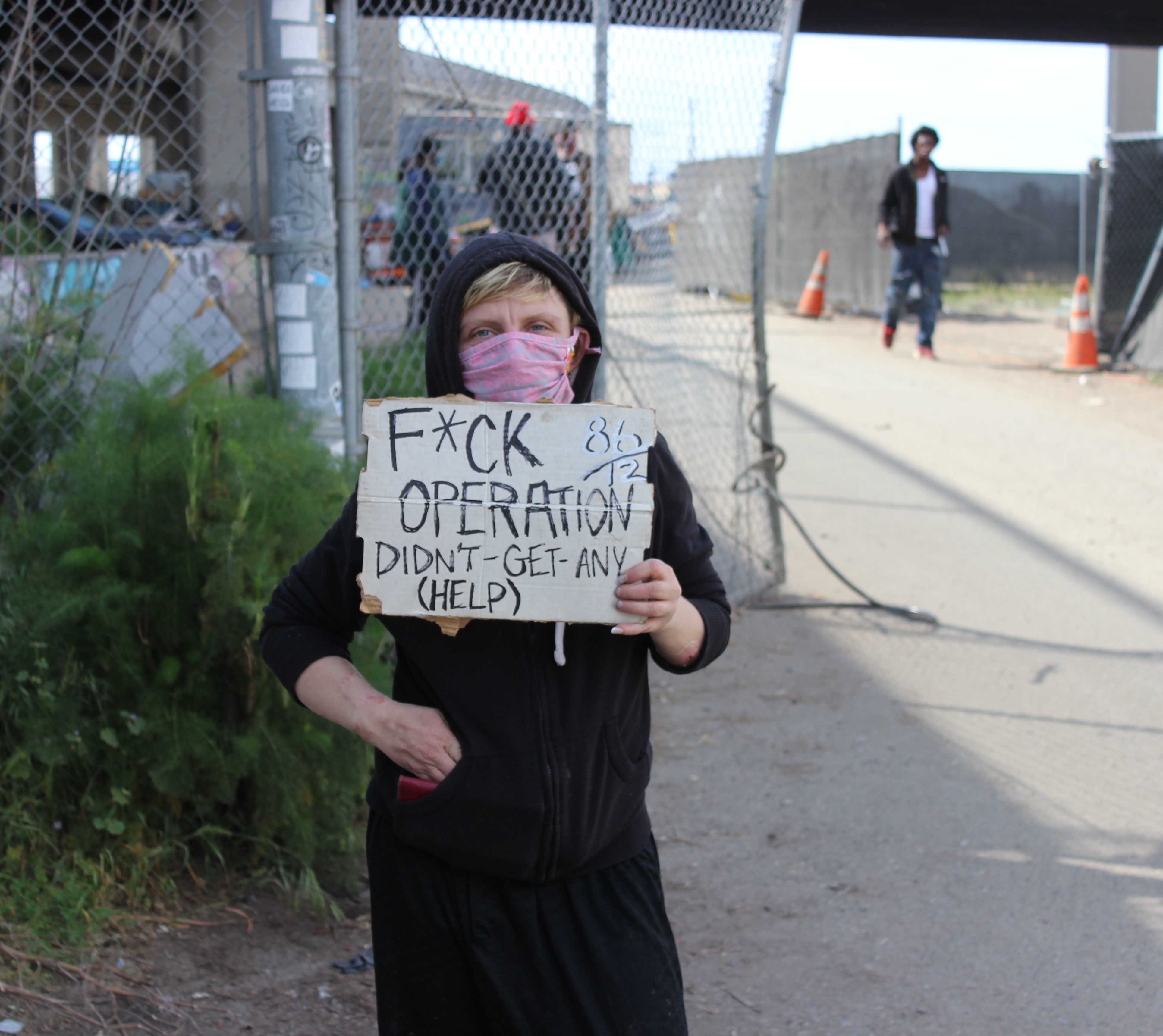

Bailey’s lived mostly on and off of Wood Street for the last two years. She recently spent over three months living in the city-sanctioned Community Cabins, or as many homeless people and activists call it, the Tuff Shed program. She was unhappy with the program, which shelters two people in 10 by 12 foot sheds, but said her complaints to Operation Dignity, the non-profit that runs the site she lived at, “fell on deaf ears.”

She said that while the program had hand washing stations, they were often out of soap so residents couldn’t use them.

“What’s the point in having [hand washing stations] if you can’t use them?” she asked.

Using the microphone and amplifier, Bailey spoke at the protest of her experiences in the Tuff Shed program.

“It’s really, really sad and it speaks volumes to the situation that my husband and I had to choose to go back on the streets because it was safer than these city-paid-for programs,” she said.

In an interview with Oakland Reporter, Bailey also complained of a recent increased police presence at Wood Street. While in the past she’s been unable to get police to show up to Wood Street when she could have needed them, these days she says, “I cough the wrong way and suddenly you see two police cars show up.”

Andrews said lately he sees police on site every time he goes to Wood Street to help. He said he often sees unhoused people getting arrested.

Ford said he feels scared at the constant police presence.

“It makes me feel like running and it shouldn’t because I’ve done nothing wrong,” said Ford. “They come with intent to push or move or harm. That’s how I feel. And I’ve seen that.”

As activists heard police sirens in the distance, the protest, which lasted less than ten minutes, ended abruptly. Those who participated met near Fruitvale’s Safeway for a socially- distanced debrief about the protest.

Poet, journalist, substitute teacher writing mostly about homelessness.